what smaller political parties joined to form the populists apush

| People's Party | |

|---|---|

| Leader |

|

| Founded | 1892 (1892) |

| Dissolved | 1909 (1909) |

| Merger of |

|

| Preceded past |

|

| Succeeded past | Democratic Party |

| Credo |

|

| Political position | Left-wing |

| |

The People'south Party, also known as the Populist Party or just the Populists, was a left-wing[ii] agrarian populist[3] belatedly-19th-century political political party in the Usa. The Populist Party emerged in the early 1890s as an important force in the Southern and Western U.s.a., but collapsed afterward it nominated Democrat William Jennings Bryan in the 1896 U.s. presidential ballot. A rump faction of the party continued to operate into the first decade of the 20th century, but never matched the popularity of the party in the early 1890s.

The Populist Party'south roots lay in the Farmers' Brotherhood, an agrarian move that promoted economic activeness during the Gilded Age, equally well as the Greenback Party, an earlier 3rd party that had advocated fiat money. The success of Farmers' Brotherhood candidates in the 1890 elections, along with the conservatism of both major parties, encouraged Farmers' Alliance leaders to plant a full-fledged third party before the 1892 elections. The Ocala Demands laid out the Populist platform: commonage bargaining, federal regulation of railroad rates, an expansionary monetary policy, and a Sub-Treasury Plan that required the establishment of federally controlled warehouses to aid farmers. Other Populist-endorsed measures included bimetallism, a graduated income tax, direct election of Senators, a shorter workweek, and the establishment of a postal savings system. These measures were collectively designed to curb the influence of monopolistic corporate and financial interests and empower minor businesses, farmers and laborers.

In the 1892 presidential election, the Populist ticket of James B. Weaver and James G. Field won viii.five% of the popular vote and carried four Western states, becoming the starting time third party since the finish of the American Civil War to win electoral votes. Despite the support of labor organizers like Eugene 5. Debs and Terence Five. Powderly, the party largely failed to win the vote of urban laborers in the Midwest and the Northeast. Over the next four years, the party connected to run country and federal candidates, edifice up powerful organizations in several Southern and Western states. Earlier the 1896 presidential election, the Populists became increasingly polarized between "fusionists," who wanted to nominate a joint presidential ticket with the Democratic Party, and "mid-roaders," like Mary Elizabeth Lease, who favored the continuation of the Populists as an independent tertiary party. Afterwards the 1896 Democratic National Convention nominated William Jennings Bryan, a prominent bimetallist, the Populists also nominated Bryan but rejected the Democratic vice-presidential nominee in favor of party leader Thomas Due east. Watson. In the 1896 election, Bryan swept the South and Due west but lost to Republican William McKinley by a decisive margin.

Later on the 1896 presidential election, the Populist Party suffered a nationwide collapse. The party nominated presidential candidates in the three presidential elections afterwards 1896, but none came close to matching Weaver's operation in 1892. Onetime Populists became inactive or joined other parties. Other than Debs and Bryan, few politicians associated with the Populists retained national prominence.

Historians see the Populists every bit a reaction to the ability of corporate interests in the Gilt Age, simply they argue the caste to which the Populists were anti-modern and nativist. Scholars also continue to fence the magnitude of influence the Populists exerted on later organizations and movements, such as the progressives of the early 20th century. Most of the Progressives, such as Theodore Roosevelt, Robert La Follette, and Woodrow Wilson, were bitter enemies of the Populists. In American political rhetoric, "populist" was originally associated with the Populist Party and related left-fly movements, but get-go in the 1950s it began to take on a more generic meaning, describing whatsoever anti-institution movement regardless of its position on the left–right political spectrum.

Origins [edit]

3rd political party antecedents [edit]

Ideologically, the Populist Party originated in the debate over budgetary policy in the backwash of the American Civil War. In club to fund that war, the U.S. government had left the golden standard by issuing fiat paper currency known as Greenbacks. After the war, the Eastern fiscal institution strongly favored a return to the aureate standard for both ideological reasons (they believed that money must exist backed by gold which, they argued, had intrinsic value) and economic proceeds (a return to the gold standard would make their government bonds more valuable).[4] Successive presidential administrations favored "difficult money" policies that retired the greenbacks, thereby shrinking the corporeality of currency in circulation.[five] Financial interests also won passage of the Coinage Act of 1873, which barred the coinage of silver, thereby ending a policy of bimetallism.[vi] The deflation caused past these policies affected farmers peculiarly strongly, since deflation made it more than difficult to pay debts and led to lower prices for agricultural products.[vii]

Angered by these developments, some farmers and other groups began calling for the government to permanently prefer fiat currency. These advocates of "soft money" were influenced by economist Edward Kellogg and Alexander Campbell, both of whom advocated for fiat money issued by a primal bank.[8] Despite trigger-happy partisan rivalries, the two major parties were both closely centrolineal with business interests and supported largely like economic policies, including the gold standard.[9] The Democratic Party'due south 1868 platform endorsed the connected apply of greenbacks, merely the party embraced difficult money policies later on the 1868 election.[10]

Though soft money forces were able to win some back up in the West, launching a third political party proved difficult in the rest of the state. The United States was deeply polarized by the sectional politics of the post-Civil War era; well-nigh Northerners remained firmly fastened to the Republican Political party, while near Southerners identified with the Autonomous Party.[11] In the 1870s advocates of soft money formed the Greenback Party, which chosen for the continued apply of paper money likewise as the restoration of bimetallism.[x] Greenback nominee James B. Weaver won over three pct of the vote in the 1880 presidential election, but the Greenback Political party was unable to build a durable base of operations of support, and information technology collapsed in the 1880s.[11] Many former Greenback Political party supporters joined the Spousal relationship Labor Party, merely it also failed to win widespread support.[ citation needed ]

Farmer's Alliance [edit]

A group of farmers formed the Farmers' Alliance in Lampasas, Texas in 1877, and the organization quickly spread to surrounding counties. The Farmers' Brotherhood promoted collective economic action by farmers in society to cope with the crop-lien system, which left economic power in the hands of a mercantile elite that furnished goods on credit.[12] The movement became increasingly popular throughout Texas in the mid-1880s, and membership in the organization grew from 10,000 in 1884 to l,000 at the end of 1885. At the same fourth dimension, the Farmer's Alliance became increasingly politicized, with members attacking the "money trust" as the source and beneficiary of both the ingather lien system and deflation.[thirteen] In the hopes of cementing an alliance with labor groups, the Farmer'south Alliance supported the Knights of Labor in the Great Southwest railroad strike of 1886.[14] That same twelvemonth, a Farmer'south Alliance convention issued the Cleburne Demands, a serial of resolutions that called for, among other things, commonage bargaining, federal regulation of railroad rates, an expansionary monetary policy, and a national banking system administered by the federal regime.[15]

President Grover Cleveland's veto of a Texas seed bill in early 1887 outraged many farmers, encouraging the growth of a northern Farmer'south Alliance in states like Kansas and Nebraska.[sixteen] That same year, a prolonged drought began in the West, contributing to the defalcation of many farmers.[17] In 1887, the Farmer's Brotherhood merged with the Louisiana Farmers Matrimony and expanded into the Southward and the Groovy Plains.[18] In 1889, Charles Macune launched the National Economist, which became the national paper of the Farmer's Alliance.[nineteen]

Macune and other Farmer's Alliance leaders helped organize a December 1889 convention in St. Louis; the convention met with the goal of forming a confederation of the major farm and labor organizations.[twenty] Though a total merger was non achieved, the Farmer's Alliance and the Knights of Labor jointly endorsed the St. Louis Platform, which included many of the long-continuing demands of the Farmer's Alliance. The Platform added a call for Macune's "Sub-Treasury Plan," nether which the federal regime would establish warehouses in agricultural counties; farmers would be allowed to store their crops in these warehouses and borrow upwards to 80 percentage of the value of their crops.[21] The movement began to expand into the Northeast and the Nifty Lakes region, while Macune led the establishment of the National Reform Press Association, a network of newspapers sympathetic to the Farmer's Alliance.[22]

Formation [edit]

The Farmer's Alliance had initially sought to piece of work within the two-political party organisation, but by 1891 many party leaders had get convinced of the need for a third party that could challenge the conservatism of both major parties.[23] In the 1890 elections, Farmer's Alliance-backed candidates won dozens of races for the U.Due south. House of Representatives and gained majorities in several state legislatures.[24] Many of these individuals were elected in coalition with Democrats; in Nebraska, the Farmer'southward Brotherhood forged an alliance with newly elected Congressman William Jennings Bryan, while in Tennessee, local Farmer's Brotherhood leader John P. Buchanan was elected governor on the Democratic ticket.[25] As most leading Democrats refused to endorse the Sub-Treasury, many leaders of the Farmer'south Alliance remained dissatisfied with both major parties.[26]

In December 1890, a Farmer's Alliance convention re-stated the organization's platform with the Ocala Demands; Farmer's Alliance leaders also agreed to hold another convention in early 1892 to discuss the possibility of establishing a third party if Democrats failed to adopt their policy goals.[27] Amidst those who favored the establishment of a third political party were Farmer's Alliance president Leonidas Fifty. Polk, Georgia newspaper editor Thomas E. Watson, and erstwhile Congressman Ignatius L. Donnelly of Minnesota.[28]

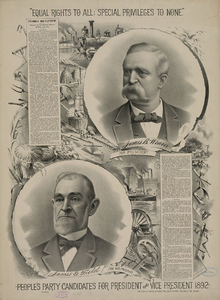

1892 People'due south Party entrada affiche promoting James Weaver for President of the United States

The February 1892 Farmer's Alliance convention was attended by supporters of Edward Bellamy and Henry George,[29] also as current and former members of the Greenback Political party, Prohibition Party, Anti-Monopoly Party, Labor Reform Party, Spousal relationship Labor Party, United Labor Party, Workingmen Party, and dozens of other minor parties. Delivering the final speech of the convention, Ignatius 50. Donnelly, stated, "We meet in the midst of a nation brought to the verge of moral, political, and fabric ruin. ... We seek to restore the government of the republic to the hands of the 'evidently people' with whom it originated. Our doors are open to all points of the compass. ... The interests of rural and urban labor are the same; their enemies are identical."[30] Following Donnelly'southward speech, delegates agreed to establish the People's Political party and agree a presidential nominating convention on July iv in Omaha, Nebraska.[31] Journalists covering the fledgling party began referring to it as the "Populist Party," and that term quickly became widely popular.[2]

1892 election [edit]

1892 balloter vote results

The initial front-runner for the Populist Party's presidential nomination was Leonidas Polk, who had served as the chairman of the convention in St. Louis, just he died of an illness weeks before the Populist convention.[32] The political party instead turned to sometime Union General and 1880 Greenback presidential nominee James B. Weaver of Iowa, nominating him on a ticket with former Confederate army officer James G. Field of Virginia.[33] The convention agreed to a party platform known every bit the Omaha Platform, which proposed the implementation of the Sub-Treasury and other longtime Farmer's Brotherhood goals.[34] The platform also chosen for a graduated income tax, directly election of Senators, a shorter workweek, restrictions on clearing to the U.s., and public buying of railroads and communication lines.[35]

The Populists appealed most strongly to voters in the Southward, the Great Plains, and the Rocky Mountains.[36] In the Rocky Mountains, Populist voters were motivated past support for complimentary silver (bimetallism), opposition to the power of railroads, and clashes with large landowners over h2o rights.[37] In the South and the Great Plains, Populists had a broad appeal among farmers, simply relatively trivial support in cities and towns. Businessmen and, to a lesser extent, skilled craftsmen were appalled by the perceived radicalism of Populist proposals. Fifty-fifty in rural areas, many voters resisted casting bated their long-standing partisan allegiances.[38] Turner concludes that Populism appealed most strongly to economically distressed farmers who were isolated from urban centers.[39] Linda Slaughter, a prominent women'south rights advocate from the Dakota Territory, too participated in the convention, making her the first American adult female to vote for a presidential candidate at a national convention.[forty]

I of the Populist Party's central goals was to create a coalition between farmers in the South and Westward and urban laborers in the Midwest and Northeast. In the latter regions, the Populists received the support of matrimony officials similar Knights of Labor leader Terrence Powderly and railroad organizer Eugene V. Debs, equally well equally author Edward Bellamy's Nationalist Clubs. Only the Populists lacked compelling campaign planks that appealed specifically to urban laborers, and were largely unable to mobilize back up in urban areas. Corporate leaders had largely been successful in preventing labor from organizing politically and economically, and wedlock membership did not rival that of the Farmer'due south Brotherhood. Some unions, including the fledgling American Federation of Labor, refused to endorse any party.[41] Populists were also largely unable to win the back up of farmers in the Northeast and the more adult parts of the Midwest.[42]

In the 1892 presidential election, Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland, a stiff supporter of the golden standard, defeated incumbent Republican President Benjamin Harrison.[43] Weaver won over one 1000000 votes, carried Colorado, Kansas, Idaho, and Nevada, and received balloter votes from Oregon and Northward Dakota. He was the first third-political party candidate since the Civil State of war to win electoral votes,[44] while Field was first Southern candidate to win electoral votes since the 1872 election.[ commendation needed ] The Populists performed strongly in the West, only many party leaders were disappointed past the results in parts of the South and the entire Great Lakes Region.[45] Weaver failed to win more than 5% of the vote in whatever land eastward of the Mississippi River and north of the Mason–Dixon line.[46]

Between presidential elections, 1893–1895 [edit]

Shortly after Cleveland took role, the country brutal into a deep recession known equally the Panic of 1893. In response, Cleveland and his Democratic allies repealed the Sherman Silverish Purchase Act and passed the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act, which provided for a minor reduction in tariff rates.[46] The Populists denounced the Cleveland administration'due south connected adherence to the gold standard, and they angrily attacked the administration's decision to purchase gold from a syndicate led by J. P. Morgan. Millions brutal into unemployment and poverty, and groups similar Coxey's Regular army organized protest marches in Washington, D.C.[47] Political party membership grew in several states; historian Lawrence Goodwyn estimates that in the mid-1890s the party had "a post-obit of anywhere from 25 to 45 pct of the electorate in xx-odd states."[48] Partly due to the growing popularity of the Populist movement, the Democratic Congress included a provision to re-implement a federal income tax in the 1894 Wilson–Gorman Tariff Human activity.[49] [a]

The Populists faced challenges from both the established major parties and the "Silverites," who more often than not overlooked the Omaha Platform in favor of bimetallism. These Silverites, who formed groups like the Silver Party and the Silver Republican Party, became particularly potent in Western mining states like Nevada and Colorado.[50] In Colorado, Populists elected Davis Hanson Waite as governor, just the party divided over the Waite's refusal to suspension the Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894.[51] Silverites were also stiff in Nebraska, where Democratic Congressman William Jennings Bryan connected to savor the support of many Nebraska Populists. A coalition of Democrats and Populists elected Populist William V. Allen to the Senate.[50]

The 1894 elections were a massive defeat for the Democratic Party throughout the land, and a mixed result for the Populists. Populists performed poorly in the West and Midwest, where Republicans dominated, but won elections in Alabama and other states. In the aftermath, some party leaders, particularly those exterior the South, became convinced of the need to fuse with Democrats and adopt bimetallism as the party's fundamental issue. Political party chairman Herman Taubeneck alleged that the party should carelessness the Omaha Platform and "unite the reform forces of the nation" behind bimetallism.[52] Meanwhile, leading Democrats increasingly distanced themselves from Cleveland'due south aureate standard policies in the aftermath of their operation in the 1894 elections.[53]

The Populists became increasingly polarized between moderate "fusionists" like Taubeneck and radical "mid-roaders" (named for their desire to take a middle road betwixt Democrats and Republicans) similar Tom Watson.[54] Fusionists believed the perceived radicalism of the Omaha Platform limited the political party's appeal, whereas a platform based on free silver would resonate with a wide array of groups.[55] The mid-roaders believed that free silver did not represent serious economic reform, and continued to call for authorities buying of railroads, major changes to the financial organisation, and resistance to the influence of big corporations.[56] One Texas Populist wrote that free silver would "go out undisturbed all the conditions which give rise to the undue concentration of wealth. The and so-chosen silverish party may bear witness a veritable Trojan Horse if we are not careful."[57] In an endeavor to get the party to repudiate the Omaha Platform in favor of free silver, Taubeneck called a political party convention in Dec 1894. Rather than repudiating the Omaha Platform, the convention expanded it to include a call for the municipal ownership of public utilities.[58]

Populist-Republican fusion in North Carolina [edit]

In 1894–1896 the Populist wave of agrestal unrest swept through the cotton and tobacco regions of the South.[59] The most dramatic impact was in North Carolina, where the poor white farmers who comprised the Populist political party formed a working coalition with the Republican Party, then largely controlled by blacks in the low country, and poor whites in the mountain districts. They took control of the country legislature in both 1894 and 1896, and the governorship in 1896. Restrictive rules on voting were repealed. In 1895 the legislature rewarded its black allies with patronage, naming 300 blackness magistrates in eastern districts, too as deputy sheriffs and city policemen. They as well received some federal patronage from the coalition congressman, and land patronage from the governor.[60]

Women and African Americans [edit]

Due to the prevailing racist attitudes of the tardily 19th century, any political brotherhood of Southern blacks and Southern whites was difficult to construct, just shared economic concerns immune some transracial coalition building.[61] Subsequently 1886, blackness farmers started organizing local agricultural groups forth the lines the Farmer's Alliance advocated, and in 1888 the national Colored Alliance was established.[62] Some southern Populists, including Watson, openly spoke of the need for poor blacks and poor whites to set aside their racial differences in the proper name of shared economic interests. The Populists followed the Prohibition Party in actively including women in their diplomacy. Merely regardless of these appeals, racism did non evade the People's Political party. Prominent Populist Party leaders such as Marion Butler at least partially demonstrated a dedication to the cause of white supremacy, and in that location appears to have been some support for this viewpoint in the political party's rank-and-file membership.[63] Subsequently 1900 Watson himself became an outspoken white supremacist.

Conspiratorial tendencies [edit]

Historians proceed to fence the caste to which the Populists were bigoted against foreigners and Jews.[64] Members of the anti-Cosmic American Protective Association were influential in California'southward Populist Party organisation, and some Populists embraced the anti-Semitic conspiracy theory that the Rothschild family unit sought to control the United States.[65] Historian Hasia Diner says:

- Some Populists believed that Jews made upward a grade of international financiers whose policies had ruined small family farms, they asserted, owned the banks and promoted the gilded standard, the chief sources of their impoverishment. Agrarian radicalism posited the urban center equally antonymous to American values, asserting that Jews were the essence of urban corruption.[66]

Presidential election of 1896 [edit]

In 1896, the 36-year-sometime William Jennings Bryan was the chosen candidate resulting from the fusion of the Democrats and the People's Party.

In the lead-up to the 1896 presidential election, mid-roaders, fusionists, and gratuitous silvery Democrats all maneuvered to put their favored candidates in the best position to win. Mid-roaders sought to ensure that the Populists would hold their national convention before that of the Autonomous Party, thereby ensuring that they could not be defendant of dividing "reform" forces.[67] Defying those hopes, Taubeneck arranged for the 1896 Populist National Convention to have place one week afterwards the 1896 Democratic National Convention.[67] Mid-roaders mobilized to defeat the fusionists; the Southern Mercury urged readers to nominate convention delegates who would "back up the Omaha Platform in its entirety."[68] As most of the party'southward high-ranking officeholders were fusionists, the mid-roaders faced difficulty in uniting around a candidate.[69]

The 1896 Republican National Convention nominated William McKinley, a long-time Republican leader who was best known for leading the passage of 1890 McKinley Tariff. McKinley initially sought to downplay the gilded standard in favor of candidature on higher tariff rates, but he agreed to fully endorse the gold standard at the insistence of Republican donors and party leaders.[70] Coming together later in the yr, the 1896 Democratic National Convention nominated William Jennings Bryan for president after Bryan's Cantankerous of Aureate speech communication galvanized the party behind gratis argent. For vice president, the party nominated conservative aircraft magnate Arthur Sewall.[71]

When the Populist convention met, fusionists proposed that the Populists nominate the Democratic ticket, while mid-roaders organized to defeat fusionist efforts. Every bit Sewall was objectionable to many inside the party, the mid-roaders successfully moved a movement to nominate the vice president get-go. Despite a telegram from Bryan indicating that he would non take the Populist nomination if the political party did not also nominate Sewall, the convention chose Tom Watson equally the party's vice presidential nominee. The convention also reaffirmed the major planks of the 1892 platform and added back up for initiatives and referendums.[72] When the convention'south presidential election began, information technology was nevertheless unclear whether Bryan would be nominated for president and whether Bryan would have the nomination if offered. Mid-roaders put forward their own candidate, obscure paper editor S. F. Norton, just Norton was unable to win the support of many delegates. After a long and contentious series of roll telephone call votes, Bryan won the Populist presidential nomination, taking 1042 votes to Norton's 321 votes.[73]

Despite his earlier proclamation, Bryan accepted the Populist nomination.[74] Facing a massive financial and organizational disadvantage,[75] Bryan embarked on a campaign that took him beyond the land. He largely ignored major cities and the Northeast, instead focusing on the Midwest, which he hoped to win in conjunction with the Slap-up Plains, the Far West, and the S.[76] Watson, ostensibly Bryan's running mate, campaigned on a platform of "Directly Populism" and frequently attacked Sewall as an agent for "the banks and railroads." He delivered several speeches in Texas and the Midwest earlier returning to his home in Georgia for the residue of the ballot.[74]

Ultimately, McKinley won a decisive majority of the balloter vote and became the first presidential candidate to win a majority of the pop vote since the 1876 presidential ballot.[76] Bryan swept the old Populist strongholds in the W and S, and added the silverite states in the West, but did poorly in the industrial heartland. His strength was largely based on the traditional Democratic vote, but he lost many German language Catholics and members of the middle class. Historians believe his defeat was partly attributable to the tactics Bryan used; he had aggressively "run" for president, while traditional candidates would use "front end porch campaigns."[77] [ folio needed ] The united opposition of nearly all business leaders and about religious leaders also injure his candidacy, as did his poor showing among Catholic groups who were alienated by Bryan'due south emphasis on Protestant moral values.[76]

Plummet [edit]

People's Party campaign affiche from 1904 touting the candidacy of Thomas Eastward. Watson

The Populist movement never recovered from the failure of 1896, and national fusion with the Democrats proved disastrous to the political party. In the Midwest, the Populist Party essentially merged into the Autonomous Party before the end of the 1890s.[78] In the South, the National brotherhood with the Democrats sapped the Populists' ability to remain independent. Tennessee's Populist Political party was demoralized by a diminishing membership, and puzzled and split past the dilemma of whether to fight the state-level enemy (the Democrats) or the national foe (the Republicans and Wall Street). By 1900 the People'due south Party of Tennessee was a shadow of what information technology one time was.[79] [ page needed ] A similar blueprint repeated throughout the South, where the Populist Party had previously sought alliances with the Republican Party confronting the ascendant land Democrats, including in Watson'due south Georgia.

In North Carolina, the country Democratic Political party orchestrated a propaganda campaign in newspapers beyond the state, and created a brutal and fierce white supremacy ballot campaign to defeat the North Carolina Populists and GOP, the Fusionist revolt in North Carolina complanate in 1898, and white Democrats returned to power. The gravity of the crisis was underscored by a major race riot in Wilmington in 1898, two days after the election. Knowing they had simply retaken control of the country legislature, the Democrats were confident they could not be overcome. They attacked and overcame the Fusionists; mobs roamed the black neighborhoods, shooting, killing, burning buildings, and making a special target of the blackness paper.[80] In that location were no farther insurgencies in whatsoever Southern states involving a successful black coalition at the state level. By 1900, the gains of the populist-Republican coalition were reversed, and the Democrats ushered in disfranchisement:[81] practically all blacks lost their vote, and the Populist-Republican alliance fell autonomously.

In 1900, many Populist voters supported Bryan again (though Marion Butler'south home county of Sampson swung heavily to Republican McKinley in a backlash against the state Autonomous party), just the weakened party nominated a carve up ticket of Wharton Barker and Ignatius 50. Donnelly, and disbanded afterward.[ citation needed ] The prosperity of the first decade of the 1900s helped ensure that the party continued to fade abroad.[82] Populist activists retired from politics, joined a major political party, or followed Debs into the Socialist Party.

In 1904, the political party was reorganized, and Watson was its nominee for president in 1904 and 1908, later which the political party disbanded again.

In A Preface to Politics, published in 1913, Walter Lippmann wrote, "As I write, a convention of the Populist Party has just taken place. Eight delegates attended the meeting, which was held in a parlor."[83] This may record the last gasp of the political party arrangement.

Legacy [edit]

Fence by historians [edit]

Since the 1890s historians have vigorously debated the nature of Populism.[84] Some historians run into the populists as forward-looking liberal reformers, others every bit reactionaries trying to recapture an idyllic and utopian past. For some they were radicals out to restructure American life, and for others they were economically difficult-pressed agrarians seeking government relief. Much recent scholarship emphasizes Populism'south debt to early American republicanism.[85] Clanton (1991) stresses that Populism was "the terminal significant expression of an erstwhile radical tradition that derived from Enlightenment sources that had been filtered through a political tradition that bore the distinct banner of Jeffersonian, Jacksonian, and Lincolnian commonwealth." This tradition emphasized human rights over the greenbacks nexus of the Gilded Historic period'due south dominant credo.[86]

Frederick Jackson Turner and a succession of western historians depicted the Populist as responding to the closure of the frontier. Turner wrote:

- The Farmers' Brotherhood and the Populist need for regime ownership of the railroad is a phase of the same endeavour of the pioneer farmer, on his latest frontier. The proposals take taken increasing proportions in each region of Western Advance. Taken as a whole, Populism is a manifestation of the old pioneer ethics of the native American, with the added chemical element of increasing readiness to use the national regime to outcome its ends.[87]

The most influential Turner student of Populism was John D. Hicks, who emphasized economic pragmatism over ideals, presenting Populism equally involvement grouping politics, with have-nots demanding their off-white share of America's wealth which was being leeched off by nonproductive speculators. Hicks emphasized the drought that ruined so many Kansas farmers, but besides pointed to financial manipulations, deflation in prices caused past the gilded standard, loftier interest rates, mortgage foreclosures, and high railroad rates. Corruption accounted for such outrages and Populists presented popular control of government as the solution, a point that later students of republicanism emphasized.[88] In the 1930s, C. Vann Woodward stressed the southern base of operations, seeing the possibility of a blackness-and-white coalition of poor against the overbearing rich.[89]

In the 1950s, scholars such as Richard Hofstadter portrayed the Populist motility every bit an irrational response of backward-looking farmers to the challenges of modernity. Though Hofstadter wrote that the Populists were the "outset modern political move of practical importance in the U.s.a. to insist that the federal regime had some responsibility for the common weal", he criticized the movement as anti-Semitic, conspiracy-minded, nativist, and grievance-based.[9] Co-ordinate to Hofstadter, the antithesis of anti-modern Populism was the modernizing nature of Progressivism. Hofstadter noted that leading progressives similar Theodore Roosevelt, Robert La Follette Sr., George Norris and Woodrow Wilson were vehement enemies of Populism, though Bryan cooperated with them and accustomed the Populist nomination in 1896.[ninety] [ page needed ] Reichley (1992) sees the Populist Political party primarily every bit a reaction to the decline of the political hegemony of white Protestant farmers; the share of farmers in the workforce had fallen from about 70% in the early on 1830s to about 33% in the 1890s. Reichley argues that, while the Populist Party was founded in reaction to economic hardship, by the mid-1890s it was "reacting not just against the coin power but against the whole globe of cities and alien customs and loose living they felt was challenging the agrarian manner of life."[65]

Goodwyn (1976)[91] [ page needed ] and Postel (2007) reject the notion that the Populists were traditionalistic and anti-modernistic. Rather, they debate, the Populists aggressively sought self-consciously progressive goals. Goodwyn criticizes Hofstadter'southward reliance on secondary sources to narrate the Populists, working instead with material generated by the Populists themselves. Goodwyn determines that the farmers' cooperatives gave rise to a Populist culture, and their efforts to complimentary farmers from lien merchants revealed to them the political structure of the economic system, which propelled them into politics. The Populists sought diffusion of scientific and technical noesis, formed highly centralized organizations, launched large-scale incorporated businesses, and pressed for an array of state-centered reforms. Hundreds of thousands of women committed to Populism, seeking a more modern life, education, and employment in schools and offices. A large section of the labor movement looked to Populism for answers, forging a political coalition with farmers that gave impetus to the regulatory state. Progress, however, was besides menacing and inhumane, Postel notes. White Populists embraced social-Darwinist notions of racial improvement, Chinese exclusion and separate-but-equal.[92] [ page needed ]

Influence on later movements [edit]

Populist voters remained agile in the electorate long after 1896, but historians continue to fence which party, if whatsoever, absorbed the largest share of them. In a instance study of California Populists, historian Michael Magliari constitute that Populist voters influenced reform movements in California'due south Democratic Political party and Socialist Party, merely had a smaller touch on on California'south Republican Political party.[93] In 1990, historian William F. Holmes wrote, "an earlier generation of historians viewed Populism as the initiator of twentieth-century liberalism as manifested in Progressivism, merely over the past two decades we have learned that fundamental differences separated the ii movements."[94] Most of the leading progressives (except Bryan) fiercely opposed Populism. Theodore Roosevelt, Norris, La Follette, William Allen White and Wilson all strongly opposed Populism. It is debated whether any Populist ideas made their style into the Democratic Party during the New Bargain era. The New Deal farm programs were designed past experts (like Henry A. Wallace) who had null to do with Populism. Michael Kazin's The Populist Persuasion (1995) argues that Populism reflected a rhetorical way that manifested itself in spokesmen similar Begetter Charles Coughlin in the 1930s and Governor George Wallace in the 1960s.

Long after the dissolution of the Populist Party, other third parties, including a People'southward Party founded in 1971 and a Populist Party founded in 1984, took on similar names. These parties were not directly related to the Populist Party.

Populism equally a generic term [edit]

In the United States, the term "populist" originally referred to the Populist Political party and related left-wing movements of the late 19th century that wanted to curtail the power of the corporate and financial establishment. Later the term "populist" began to apply to whatever anti-establishment movement.[2] The original generic definition of the term, which has held consistently since the emergence of its mail-Populist Party genericness, describes a populist every bit "a believer in the rights, wisdom, or virtues of the mutual people."[95] [96] In the 21st century, the term over again began to be used. Politicians as diverse every bit independent left-fly Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Republican President Donald Trump accept been labeled populists.

Balloter history and elected officials [edit]

Presidential tickets [edit]

| Year | Presidential nominee | Home state | Previous positions | Vice presidential nominee | Home state | Previous positions | Votes | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1892 |  James B. Weaver | | Member of the U.S. Business firm of Representatives from Iowa'due south 6th congressional district (1879–1881; 1885–1889) Greenback Political party nominee for President of the United States (1880) |  James G. Field | | Chaser Full general of Virginia (1877–1882) | ane,026,595 (8.5%) 22 EV | [97] |

| 1896 |  William Jennings Bryan | | Fellow member of the U.S. Business firm of Representatives from Nebraska'southward 1st congressional district (1891–1895) |  Thomas E. Watson | | Fellow member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 10th congressional district (1891–1893) | 222,583 (1.half-dozen%) 27 EV | [98] |

| 1900 |  Wharton Barker | | Financier, publicist |  Ignatius L. Donnelly | | Lieutenant Governor of Minnesota (1860–1863) Member of the U.Southward. House of Representatives from Minnesota'due south 2nd congressional commune (1863–1869) Member of the Minnesota Senate (1875–1879; 1891–1895) Fellow member of the Minnesota Firm of Representatives (1887–1889; 1897–1899) | 50,989 (0.iv%) 0 EV | [99] |

| 1904 |  Thomas E. Watson | | (see to a higher place) |  Thomas Tibbles | | Journalist | 114,070 (0.8%) 0 EV | [100] |

| 1908 |  Thomas Eastward. Watson | | (run across above) |  Samuel Williams | | Approximate | 28,862 (0.2%) 0 EV | [101] |

Seats in Congress [edit]

| Election year | House of Representatives | Senate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seats after ballot | +/– | Seats after ballot | +/– | |

| 1890 | viii / 356 | New | 1 / 88 | New |

| 1892 | eleven / 356 | | 3 / 88 | |

| 1894 | ix / 357 | | iv / 88 | |

| 1896 | 22 / 357 | | five / 90 | |

| 1898 | half-dozen / 357 | | 4 / ninety | |

| 1900 | five / 357 | | iv / 90 | |

| 1902 | 0 / 357 | | 0 / ninety | |

Governors [edit]

- Colorado: Davis Hanson Waite, 1893–1895

- Idaho: Frank Steunenberg, 1897–1901 (fusion of Democrats and Populists)

- Kansas: Lorenzo D. Lewelling, 1893–1895

- Kansas: John W. Leedy, 1897–1899

- Nebraska: Silas A. Holcomb, 1895–1899 (fusion of Democrats and Populists)

- Nebraska: William A. Poynter, 1899–1901 (fusion of Democrats and Populists)

- North Carolina: Daniel Lindsay Russell, 1897–1901 (coalition of Republicans and Populists)

- Oregon: Sylvester Pennoyer, 1887–1895 (fusion of Democrats and Populists)

- South Dakota: Andrew E. Lee, 1897–1901

- Tennessee: John P. Buchanan, 1891–1893

- Washington: John Rogers, 1897–1901 (fusion of Democrats and Populists)

Members of Congress [edit]

Approximately xl-5 members of the party served in the U.S. Congress between 1891 and 1902. These included vi Usa Senators:

- William A. Peffer and William A. Harris from Kansas

- Marion Butler of Due north Carolina

- James H. Kyle from South Dakota

- Henry Heitfeld of Idaho

- William Five. Allen from Nebraska

The following were Populist members of the U.S. Business firm of Representatives:

52nd U.s. Congress

- Thomas E. Watson, Georgia's 10th congressional district

- Benjamin Hutchinson Clover, Kansas'southward 3rd congressional district

- John Grant Otis, Kansas's 4th congressional commune

- John Davis, Kansas's 5th congressional district

- William Baker, Kansas'south 6th congressional commune

- Jerry Simpson, Kansas's 7th congressional district

- Kittel Halvorson, Minnesota's 5th congressional district

- William A. McKeighan, Nebraska's 2nd congressional commune

- Omer Madison Kem, Nebraska'southward 3rd congressional district

53rd The states Congress

- Haldor Boen, Minnesota'southward 7th congressional district

- Marion Cannon, California's 6th congressional district

- Lafayette Pence, Colorado'due south 1st congressional district

- John Calhoun Bell, Colorado'south 2nd congressional district

- Thomas Jefferson Hudson, Kansas's tertiary congressional commune

- John Davis, Kansas' 5th congressional district

- William Bakery, Kansas' sixth congressional district

- Jerry Simpson, Kansas' 7th congressional district

- William A. Harris, Kansas Member-at-big

- William A. McKeighan, Nebraska's fifth congressional district

- Omer Madison Kem, Nebraska'southward 6th congressional district

- Alonzo C. Shuford, N Carolina'southward 7th congressional commune

54th United States Congress

- Albert Taylor Goodwyn, Alabama's 5th congressional district

- Milford W. Howard, Alabama's seventh congressional district

- William Baker, Kansas' 6th congressional district

- Omer Madison Kem, Nebraska's sixth congressional district

- Harry Skinner, North Carolina'southward 1st congressional district

- William F. Strowd, N Carolina'southward quaternary congressional commune

- Charles H. Martin (1848–1931), North Carolina's sixth congressional district

- Alonzo C. Shuford, Northward Carolina'south 7th congressional district

55th United states Congress

- Albert Taylor Goodwyn, Alabama's 5th congressional district

- Charles A. Barlow, California's 6th congressional district

- Curtis H. Castle, California's 7th congressional district

- James Gunn, Idaho'south 1st congressional district

- Mason Summers Peters, Kansas's second congressional district

- Edwin Reed Ridgely, Kansas'due south 3rd congressional district

- William Davis Vincent, Kansas's 5th congressional district

- Nelson B. McCormick, Kansas's 6th congressional district

- Jerry Simpson, Kansas's 7th congressional commune

- Jeremiah Dunham Botkin, Kansas Member-at-large

- Samuel Maxwell, Nebraska's 3rd congressional commune

- William Ledyard Stark, Nebraska's quaternary congressional district

- Roderick Dhu Sutherland, Nebraska's 5th congressional district

- William Laury Greene, Nebraska's 6th congressional district

- Harry Skinner, North Carolina's 1st congressional district

- John Eastward. Fowler, Due north Carolina'due south 3rd congressional commune

- William F. Strowd, North Carolina's 4th congressional district

- Charles H. Martin, North Carolina's fifth congressional district

- Alonzo C. Shuford, North Carolina's 7th congressional commune

- John Edward Kelley, South Dakota's 1st congressional district

- Freeman T. Knowles, Southward Dakota's 2nd congressional commune

56th Usa Congress

- William Ledyard Stark, Nebraska's fourth congressional district

- Roderick Dhu Sutherland, Nebraska'due south 5th congressional district

- William Laury Greene, Nebraska'due south 6th congressional commune

- John Westward. Atwater, N Carolina'due south 4th congressional district

57th Usa Congress

- Thomas L. Glenn, Idaho's 1st congressional commune

- Caldwell Edwards, Montana's 1st congressional commune

- William Ledyard Stark, Nebraska's 4th congressional district

- William Neville, Nebraska'south sixth congressional commune

See also [edit]

- Left-wing populism

- List of political parties in the United States

- Political interpretations of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

- Bryant Westward. Bailey, Louisiana Populist

- Annie Le Porte Diggs (1853-1916), Populist advocate

- Leonard M. Landsborough, California Populist

Notes [edit]

- ^ The income taxation provision was struck downward by the Supreme Court in the 1895 case of Pollock five. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. [49]

References [edit]

- ^ Goodwyn (1978)

- ^ a b c Kazin, Michael (22 March 2016). "How Tin can Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders Both Be 'Populist'?". New York Times . Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Mansbridge, Jane; Macedo, Stephen (2019-x-thirteen). "Populism and Democratic Theory". Annual Review of Law and Social Science. 15 (one): 59–77. doi:10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-101518-042843. ISSN 1550-3585. S2CID 210355727.

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. ten–12

- ^ Brands (2010), pp. 432–433

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. sixteen–17

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 12, 24

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. thirteen–14

- ^ a b Zeitz, Joshua (14 January 2018). "Historians Have Long Thought Populism Was a Expert Thing. Are They Wrong?". Politico. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ a b Reichley (2000), pp. 133–134

- ^ a b Goodwyn (1978), pp. eighteen–19

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 24–26

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 32–34

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 35–41

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 46–49

- ^ Brands (2010), pp. 433–434

- ^ Reichley (2000), pp. 134–135

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 57–59, 63

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), p. ninety

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 91–92

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 107–110, 113

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 116–117

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 127–128

- ^ Brands (2010), p. 438

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 143–144

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 147–148, 159

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), p. 151

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 163–165

- ^ Brands (2010), p. 439

- ^ Kazin (1995), pp. 27–29

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 167–168, 171

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 169–172

- ^ Brands (2010), p. 440

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 172–173

- ^ Brands (2010), pp. 439–440

- ^ Holmes (1990), p. 37

- ^ Holmes (1990), pp. 30–31

- ^ Holmes (1990), pp. 35–38, 46

- ^ Turner (1980), pp. 358, 364–367

- ^ Wishart, David J. (2004). Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 337. ISBN978-0-8032-4787-one.

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 174–179

- ^ Holmes (1990), pp. 38–39

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 200–201

- ^ "Egad! He Moved His Anxiety When He Ran". The Washington Mail. 2008-07-05. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-09-10 .

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 186–187, 199–200

- ^ a b Reichley (2000), p. 138

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 207–208

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), p. 233

- ^ a b Brands (2010), pp. 485–486

- ^ a b Goodwyn (1978), pp. 215–218, 221–222

- ^ Holmes (1990), p. 50

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 227–229

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 238–239

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 230–231

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 233–234

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 234–235

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 249–250

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 241–242

- ^ Bouie, Jamelle (Baronial 14, 2019). "America holds onto an undemocratic assumption from its founding: that some people deserve more power than others". The New York Times . Retrieved 20 Baronial 2019.

Despite insurgencies at habitation — the Populist Party, for example, swept through Georgia and North Carolina in the 1890s...

- ^ Helen G. Edmonds, The Negro and Fusion Politics in Northward Carolina, 1894-1901 (1951). pp 97-136

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 121–122

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 118–120

- ^ Hunt (2003), pp. 3–7

- ^ Turner (1980), pp. 355–356

- ^ a b Reichley (2000), p. 142

- ^ Hasia R. Diner (2004). The Jews of the U.s., 1654 to 2000. U. of California Printing. p. 170. ISBN9780520227736.

- ^ a b Goodwyn (1978), pp. 247–248

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 251–252

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), p. 257

- ^ Reichley (2000), pp. 139–141

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 254–256

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 256–259

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 259–262

- ^ a b Goodwyn (1978), pp. 274–278

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 279–280

- ^ a b c Reichley (2000), pp. 144–146

- ^ R. Hal Williams, Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan, and the Remarkable Election of 1896 (2010)

- ^ Goodwyn (1978), pp. 285–286

- ^ Lester (2007)

- ^ Andrea Meryl Kirshenbaum, "'The Vampire That Hovers Over North Carolina': Gender, White Supremacy, and the Wilmington Race Riot of 1898," Southern Cultures 4#3 (1998) pp. six-30 online

- ^ Eric Anderson, Race and Politics in Northward Carolina, 1872-1901 (1981)

- ^ Brands (2010), p. 529

- ^ Walter Lippmann, A Preface to Politics, New York and London: Mitchell Kennerley, 1913, p. 275.

- ^ For a summary or how historians approach the topic see Worth Robert Miller, "A Centennial Historiography of American Populism." Kansas History 1993 sixteen(i): 54-69.

- ^ Run into Worth Robert Miller, "The Republican Tradition," in Miller, Oklahoma Populism: A History of the People'due south Political party in the Oklahoma Territory (1987) online edition

- ^ Clanton (1991), p. 15

- ^ Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History, (1920) p. 148; online edition

- ^ Martin Ridge, "Populism Revolt: John D. Hicks and The Populist Revolt," Reviews in American History thirteen (March 1985): 142-54.

- ^ C. Vann Woodward, Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (1938); Woodward, "Tom Watson and the Negro in Agrarian Politics," The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Feb., 1938), pp. 14-33 in JSTOR

- ^ Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform: From Bryan to F.D.R. (1955)

- ^ Goodwyn, Lawrence (1976). Democratic Promise: the Populist Moment in America . Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-xix-501996-four.

- ^ Postel (2007)

- ^ Magliari (1995), pp. 394, 411–412

- ^ Holmes (1990), p. 58

- ^ Webster's ninth new collegiate lexicon, Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, Inc., 1983

- ^ "Oxford English Lexicon". Oxford English language Dictionary Online. 1989. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ The ticket won 5 states; its best showing was Nevada where it received 66.8% of the vote.

- ^ The Populists nominated Bryan, the Democratic nominee, just nominated Watson for Vice President instead of Democratic nominee Arthur Sewall. Bryan and Sewall received an additional 6,286,469 (45.i%) and 149 electoral votes. Bryan'southward best showing was Mississippi, where he received 91.0% of the vote.

- ^ The ticket'south all-time result was Texas, where it received 5.0% of the vote.

- ^ The ticket's best result was Georgia, where it received 17.iii%.

- ^ The ticket'due south best result was Georgia, where it received 12.6%.

Bibliography [edit]

Secondary sources [edit]

- Ali, Omar H. (2010). In the Lion'south Mouth: Black Populism in the New Southward, 1886-1900. Academy Printing of Mississippi. ISBN9781604737806.

- Argersinger, Peter H. (2015) [1982]. Populism and Politics: William Alfred Peffer and the People's Party. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN9780813162003.

- Beeby, James G. (2008). Defection of the Tar Heels: The North Carolina Populist Motility, 1890-1901. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN9781604733242.

- Berman, David R. (2007). Radicalism in the Mount West, 1890-1920: Socialists, Populists, Miners, and Wobblies. Academy Printing of Colorado. ISBN9781607320067.

- Brands, H. Due west. (2010). American Colossus: The Triumph of Capitalism 1865-1900. Doubleday. ISBN978-0-385-52333-2.

- Clanton, O. Factor (1991). Populism: The Humane Preference in America, 1890-1900 . Twayne Publishers. ISBN9780805797442.

- Durden, Robert F. (2015) [1965]. The Climax of Populism: The Election of 1896. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN9780813162652.

- Formisano, Ronald P. (2008). For the People: American Populist Movements from the Revolution to the 1850s. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN9780807831724.

- Goodwyn, Lawrence (1978). The Populist Moment: A Brusk History of the Agrarian Revolt in America . Oxford University Press. ISBN9780199736096.

- Hackney, Sheldon, ed. (1971). Populism: the Disquisitional Issues . Little, Brown. ISBN978-0316336901.

- Hicks, John D. "The Sub-Treasury: A Forgotten Programme for the Relief of Agriculture". Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Dec., 1928), pp. 355–373. in JSTOR.

- Hicks, John D. The Populist Revolt: A History of the Farmers' Alliance and the People's Party Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1931.

- Hild, Matthew (2007). Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South. Academy of Georgia Printing. ISBN9780820328973.

- Hild, Matthew. Arkansas'southward Gilded Age: The Rise, Refuse, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest (U of Missouri Press, 2018) online review

- Holmes, William F. (1990). "Populism: In Search of Context". Agricultural History. 64 (4): 26–58. JSTOR 3743349.

- Hunt, James 50. (2003). Marion Butler and American Populism. Academy of Due north Carolina Printing. ISBN9780807862506.

- Jessen, Nathan (2017). Populism and Imperialism: Politics, Civilisation, and Foreign Policy in the American West, 1890-1900. University Press of Kansas. ISBN9780700624645.

- Kazin, Michael (1995). The Populist Persuasion . Basic Books. ISBN978-0465037933.

- Kazin, Michael (2006). A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan. Knopf. ISBN978-0375411359.

- Knoles, George Harmon. "Populism and Socialism, with Special Reference to the Ballot of 1892," Pacific Historical Review, vol. 12, no. iii (Sept. 1943), pp. 295–304. In JSTOR

- Lester, Connie (2006). Up from the Mudsills of Hell: The Farmers' Alliance, Populism, and Progressive Agriculture in Tennessee, 1870-1915. University of Georgia Press. ISBN978-0820327624.

- Magliari, Michael (1995). "What Happened to the Populist Vote? A California Case Study". Pacific Historical Review. 64 (3): 389–412. doi:x.2307/3641007. JSTOR 3641007.

- McMath, Jr., Robert C. (1993). American Populism: A Social History 1877-1898 . Macmillan. ISBN9780374522643.

- Miller, Worth Robert. "A Centennial Historiography of American Populism." Kansas History 1993 16(1): 54–69. online edition

- Miller, Worth Robert. "Farmers and Third-Party Politics in Tardily Nineteenth Century America," in Charles West. Calhoun, ed. The Gilded Age: Essays on the Origins of Modernistic America (1995) online edition

- Nugent, Walter (2013). The Tolerant Populists: Kansas Populism and Nativism (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Printing. ISBN9780226054117.

- Ostler, Jeffrey (1992). "Why the Populist Political party Was Strong in Kansas and Nebraska but Weak in Iowa". Western Historical Quarterly. 23 (4): 451–474. doi:10.2307/970302. JSTOR 970302.

- Palmer, Bruce (1980). "Human Over Money": the Southern Populist Critique of American Capitalism. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN978-0-8078-1427-7.

- Peterson, James. "The Merchandise Unions and the Populist Party," Scientific discipline & Society, vol. viii, no. ii (Bound 1944), pp. 143–160. In JSTOR.

- Pollack, Norman (1976). The Populist Response to Industrial America: Midwestern Populist Thought. Harvard University Press. ISBN9780674690516.

- Postel, Charles (2007). The Populist Vision. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN9780199758463.

- Rogers, William Warren (2001) [1970]. The One-gallused Rebellion: Agrarianism in Alabama, 1865-1896. University of Alabama Press. ISBN9780817311063.

- Stock, Catherine McNicol (2017) [1996]. Rural Radicals: Righteous Rage in the American Grain (2d ed.). Cornell University Press. ISBN9781501714054.

- Turner, James (1980). "Understanding the Populists". The Journal of American History. 67 (2): 354–373. doi:ten.2307/1890413. JSTOR 1890413.

- White, Richard (2017). The Commonwealth for Which It Stands: The United states of america During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age: 1865–1896. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN9780190619060.

- Woodward, C. Vann (2016) [1938]. Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel. Pickle Partner's Publishing. ISBN9781787202566. online edition

- Woodward, C. Vann. "Tom Watson and the Negro in Agrarian Politics," The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 4, No. 1 (February., 1938), pp. xiv–33 in JSTOR

Contemporary accounts [edit]

External links [edit]

- From People'due south Political party Platform, Omaha Morning World-Herald, five July 1892

- 40 original Populist cartoons, primary sources

- Peffer, William A. "The Mission of the Populist Party," The Due north American Review (December 1993) v. 157 #445 pp 665–679; full text online. important policy statement by leading Populist senator

- People's Political party Hand-Book of Facts. Campaign of 1898 96 p., official party pamphlet for Due north Carolina election of 1898

- Populist, republican and Democratic cartoons, 189s ballot, chief sources

- Populist Party timeline and texts; edited by Professor Edwards, secondary and primary sources

Party publications and materials

- The People's Abet (1892-1900), digitized copies of the Populist Party's paper in Washington State, from The Labor Press Projection.

- Populist Cartoon Index. Archived at Missouri State University. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- Buttons, tokens and ribbons of the Populist Party. Reprinted from Event xix, Buttons and Ballots, Fall 1998. Retrieved Baronial 26, 2006.

- People's Political party Hand-Book of Facts. Campaign of 1898: Electronic Edition. Populist Party (Northward.C.). State Executive Committee. Reformated and reprinted past the University Library, The Academy of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Populist materials online courtesy University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Secondary sources

- The Populist Movement in the United States by Anna Rochester, 1943.

- Farmers, the Populist Party, and Mississippi (1870-1900). By Kenneth Grand. McCarty. Published past Mississippi History Now a project of the Mississippi Historical Society. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- The Populist Political party in Nebraska. Published by the Nebraskastudies.org, a projection of the Nebraska Department of Educational activity.

- Fusion Politics. The Populist Party in North Carolina. A project of the John Locke Foundation. Retrieved Baronial 24, 2006.

- The Decline of the Cotton Farmer. Anecdotal account of rise and fall of Farmers Alliance and Populist Party in Texas.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/People%27s_Party_%28United_States%29

0 Response to "what smaller political parties joined to form the populists apush"

Post a Comment